For more than two centuries, women have played a vital role in the history of mountaineering in Chamonix and the surrounding Alps. Long before modern equipment and female mountain guides became the norm, these women climbed higher, pushed further and quietly rewrote what was considered possible.

Women in Mountaineering: The Pioneers of Chamonix

Below is a chronological timeline of some of the earliest and most significant female mountaineering achievements in the region. Their stories continue to inspire climbers today and paved the way for the women guiding and climbing in Chamonix now.

1786 – Elizabeth, Jane and Mary Parminter

Mont Buet

In 1786, the first recorded female mountain ascent took place in the Alps, near Vallorcine. That same year also saw the first ascent of Mont Blanc. Three women from Devon in England — sisters Elizabeth and Jane Parminter, and their cousin Mary Parminter — climbed Mont Buet.

At the time, Mont Buet had only been climbed once before, in 1770, by Jean-André Deluc, Guillaume-Antoine Deluc and Bernard Pomet. The Parminter women completed their ascent with the help of local guides Jean-Pierre Béranger and Jean-Baptiste Lombard.

Mont Buet stands at 3,096 metres and later earned the nickname “The Ladies’ Mont Blanc”, likely in recognition of this historic climb. Letters and journals from the period confirm that the Parminters became the first recorded women to climb a peak above 3,000 metres anywhere in the world.

Despite the scale of the achievement, their ascent went largely unnoticed for more than a century. It was not until 1957 that historian Gavin de Beer highlighted their climb in The Alpine Club Review, finally giving the women their place in mountaineering history.

1808 – Marie Paradis

Mont Blanc

In 1808, Marie Paradis became the first woman to reach the summit of Mont Blanc. Her ascent took place just over twenty years after the mountain’s first ascent and firmly placed her among the most well-known figures in Chamonix’s early mountain history.

Marie Paradis was a local maidservant working in a hostel on the Mont Blanc route when she met guide Jacques Balmat and two other guides. Balmat, already famous for his role in the first ascent of Mont Blanc, encouraged her to join their climb, promising recognition and reward.

Accounts from the time describe a physically brutal ascent. Marie reportedly suffered exhaustion, sickness and fear but refused to turn back. The climb took two days, and her guides are said to have supported and carried her during the final stages in poor conditions.

Despite the hardship, Marie Paradis reached the summit and earned the title of the first woman to climb Mont Blanc. Known locally as “Marie du Mont Blanc”, she became a symbol of determination and helped cement Mont Blanc’s place at the centre of both alpine legend and early mountain tourism

1838 – Henriette d’Angeville

Mont Blanc

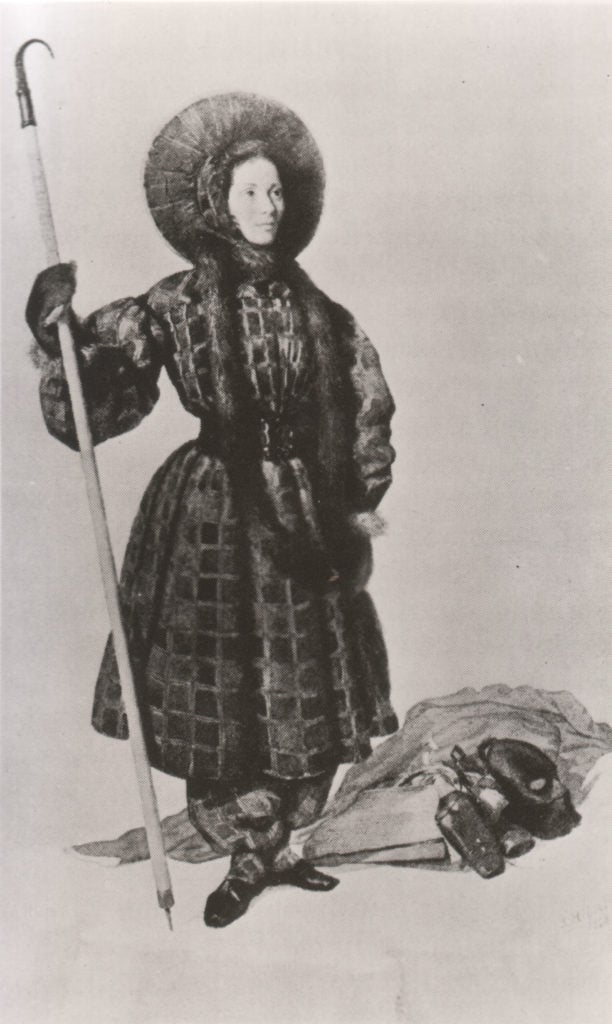

In 1838, Henriette d’Angeville successfully summited Mont Blanc, becoming one of the most influential female mountaineers of the 19th century. Unlike Marie Paradis before her, d’Angeville came from a wealthy French aristocratic family and approached the climb with careful preparation and strong intent.

At the age of 44, she organised the ascent herself and later published a detailed written account. In it, she argued that mountaineering lacked a “feminine stamp” and urged women to document their own achievements rather than let others speak for them.

Her background reflects the profile of many early female alpinists. Wealth gave d’Angeville the freedom to travel, hire guides and plan for comfort and safety. She invested heavily in her equipment and famously designed her own climbing outfit, which weighed around seven kilograms. It included knickerbocker-style trousers, a controversial choice at the time.

While Marie Paradis climbed Mont Blanc over two days in a full skirt, d’Angeville took several days and reached the summit without being carried. This distinction mattered to her contemporaries. In Chamonix, local men even placed bets on the point at which she would abandon the climb. She proved them wrong.

Because of the assistance Marie Paradis received in 1808, some later observers viewed d’Angeville’s ascent as the first “independent” female climb of Mont Blanc. Unlike Paradis, who never climbed again, d’Angeville remained an active alpinist well into her sixties.

1871 – Lucy Walker

Matterhorn (among others)

Lucy Walker came from a wealthy merchant family in Liverpool and built one of the most impressive climbing careers of her era. Over 21 years in the Alps, she completed 98 expeditions and successfully climbed 28 peaks higher than 4,000 metres.

She achieved the first female ascent of 16 major summits, including Monte Rosa, the Strahlhorn and the Grand Combin. She also became the first woman to climb the Eiger, a feat that stunned local villagers. In 1864, she completed the first recorded ascent of the Balmhorn, achieved by any climber, male or female.

Her most famous achievement came in 1871, when she became the first woman to summit the Matterhorn. At the time, the Matterhorn stood as the most coveted prize in the Alps. Walker completed the ascent with her father and local guides from Zermatt.

Despite her achievements, Lucy Walker left almost no written record of her climbs. She ignored Henriette d’Angeville’s call for women to publish their experiences. No diaries, interviews or personal accounts survive. Instead, her presence appears only in the writings of male climbers, who describe seeing her drying clothes at huts or moving confidently through deep snow in her favoured long dress.

Although she avoided publicity, Walker remained deeply involved in the mountaineering community. She became a member of the Ladies’ Alpine Club, founded in London in 1907 in response to the male-only British Alpine Club. From 1913 to 1915, she served as Vice President of the club. Lucy Walker died in 1916 at the age of 80.

1871 – Meta Brevoort

Matterhorn and others

Margaret “Meta” Brevoort came from a wealthy New York family of Dutch origin who made their fortune in property. In the late 19th century, she became one of the most prominent female alpinists of her time, second only to Lucy Walker.

The two women were closely linked by history and rivalry. When Lucy Walker heard that Brevoort was travelling to the Alps with the aim of climbing the Matterhorn, she hurried to the region herself. Walker reached the summit first in 1871, narrowly claiming the title of the first woman to climb the peak.

Brevoort arrived shortly after Walker’s ascent but did not give up. True to her reputation, she waited patiently for the right conditions. On 5 September 1871, she completed a major achievement of her own by becoming the first woman to traverse the Matterhorn from Zermatt to Breuil-Cervinia.

Over the following two weeks, she continued an extraordinary run of climbs. She became the first woman to ascend the Weisshorn (4,506m) and the Dent Blanche (4,357m).

Margaret Brevoort died young from a heart infection. At the time of her death, she was already making plans for an expedition to Everest, decades before women would be allowed to attempt it.

1871 – Emmeline Lewis Lloyd

Aiguille du Moine

Emmeline Lewis Lloyd was a regular visitor to the Alps during the 1860s and 1870s. Known for her love of fishing, otter hunting and long days in the hills, she stood out as a strong and independent character at a time when very few women climbed at all.

Unlike Lucy Walker, who usually climbed with her family, Emmeline often climbed with other women. Her main climbing partner was Isabella Charlet-Straton, after whom the Pointe Isabelle above Chamonix is named. She also climbed with her younger sister, Bessie.

Records of Emmeline’s climbs are limited, but her achievements are significant. She became the eighth woman to climb Mont Blanc. In 1871, she made the first ascent of the Aiguille du Moine (3,412m) near Chamonix, alongside Isabella Charlet-Straton and guide Joseph Simond.

That same year, the two women also climbed Monte Viso with guide Jean Charlet. Two years earlier, in 1869, they had already attempted the Matterhorn together, an ambitious goal at the time and a clear sign of their commitment to serious alpine climbing.

1876 – Isabella Charlet-Straton

Isabella Charlet-Straton became financially independent in her twenties after inheriting her family’s estate. This allowed her to travel widely and pursue mountaineering at a time when very few women could.

She began climbing with her friend Emmeline Lewis Lloyd, exploring the Alps and Pyrenees during the late 19th century. After Emmeline retired from climbing in 1873, Isabella continued with local guide Jean Charlet, whom she later married.

Together, they completed many major ascents in the Mont Blanc massif. Isabella climbed Mont Blanc four times. Her most famous achievement came in January 1876, when she completed the first winter ascent of Mont Blanc, accompanied by Jean Charlet and Sylvain Couttet.

The climb brought her international recognition and secured her place as one of the most important female mountaineers in Chamonix’s history.

1887 – Mary Mummery

The Teufelsgrat of the Täschhorn

Mary Mummery began her alpine career in the 1880s after marrying Alfred Mummery, who introduced her to mountaineering in the Alps. She quickly proved herself a natural and tackled major peaks including the Jungfrau, the Obergabelhorn and the Matterhorn.

On 15 July 1887, the couple completed one of the most demanding climbs of the era: the Teufelsgrat on the Täschhorn. Starting from Zermatt, they climbed through the night in dangerous conditions, facing rockfall, high winds and serious exposure.

The ascent became one of the most celebrated husband-and-wife achievements in mountaineering history. Alfred Mummery later insisted that Mary write the account of the climb herself, recognising her skill and courage. He also argued publicly that women were well suited to the most demanding alpine routes, challenging the limits placed on female climbers at the time.

1907 – Elizabeth le Blond

Founder of the Ladies’ Alpine Club

In 1907, Elizabeth Le Blond founded the Ladies’ Alpine Club and became its first president. By that point, she had already built a long and impressive mountaineering career.

She climbed year-round for more than 20 years, beginning in Pontresina before moving on to the Chamonix area. Her ascents included Mont Blanc, the Grandes Jorasses, and numerous winter firsts such as the Aiguille du Tour and the Aiguille du Midi. She also became the only woman of her time to lead a guideless party in winter.

Le Blond was equally influential behind the camera. She documented her climbs through photography, producing images that introduced new alpine perspectives. She later became one of the first women to experiment with filmmaking, further shaping how the mountains were seen and recorded.

1895 – Lily Bristow

First woman to climb the Grépon

During the 1890s, Lily Bristow pushed women’s climbing firmly into elite territory. She climbed frequently without guides and often led ropes made up entirely of men — something almost unheard of at the time.

Her achievements included guideless traverses of the Grand Charmoz, the Zinal Rothorn, and major routes on the Matterhorn.

In 1895, she reached the summit of the Grépon, becoming the first woman to do so. The climb crowned her career and secured her place among the strongest climbers of her generation.

1929 – Miriam O’Brien Underhill

Pioneer of “manless” climbing

Miriam O’Brien Underhill began climbing seriously in the Alps in the mid-1920s and quickly made her mark. Her early ascents included routes in the Dolomites and near Mont Blanc, several of which later became classics.

In 1929, she completed the traverse from the Aiguilles du Diable to Mont Blanc du Tacul, linking multiple 4,000-metre summits. Around the same time, she coined the term “manless climbing” to describe routes climbed entirely by women.

That same year, she and Alice Damesme completed the Grépon without male partners, causing controversy within the French climbing establishment. Undeterred, Underhill later completed a manless ascent of the Matterhorn.

She continued climbing for decades, returning to the Matterhorn for a final ascent in 1952, cementing her legacy as one of the most influential female alpinists of the 20th century.

Today’s local heroines – modern women in mountaineering

Before you take on a first ascent — or even dream of climbing the Grépon — you’ll need time on the mountain with a qualified guide. In Chamonix, a number of highly experienced female mountain guides offer instruction for all levels, from complete beginners to confident climbers looking to progress.

These women carry the legacy of the original Lady Legends forward every day. Through their work, they continue to break ground, lead major ascents and promote equality in a mountain world that remains largely male-dominated.

Fleur Fouque: Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix

Fanny Tomasi-Schmutz: Compagnie des Guides de Chamonix

Fanny Tomasi was born in Chamonix in 1987 and grew up between Chamonix and Servoz. She comes from a strong guiding background. Her father was a mountain guide and teacher at ENSA, and she later married fellow guide Damien Tomasi, who also works at ENSA.

In 2015, Fanny left her teaching career to qualify as a mountain guide. She now guides alongside her husband, sharing her deep local knowledge and passion for the mountains with her clients.

That same year, she joined Damien Tomasi, Fleur Fouque and Sébastien Rougegré for a first alpine-style ascent of the Lagunak Ridge on Ama Dablam (6,856m) in Nepal. The ascent followed a light and fast alpine approach.

Fanny continues to balance guiding in Chamonix with high-level expeditions. In 2016, she and fellow guide Elodie Lecomte completed Bhagirathi III via the Scottish Route in five days.

For first-time climbers inspired by the women in this blog, Fanny recommends the traverse of the Aiguilles Marbrées (3,535m) as an excellent introduction to alpine mountaineering.

Zoe Hart: IFMGA Mountain Leader

Zoe has spent many years in the mountains and qualified as a high mountain guide in 2007. She works across a wide range of disciplines, including mountaineering, ski touring, off-piste skiing and crevasse rescue. She also enjoys teaching and guiding families and children.

She speaks both English and French and has lived in the Chamonix valley for over 15 years. Alongside guiding, she has taught at ENSA and works in marketing for Patagonia.

Zoe is also a Patagonia Climbing Ambassador. She became the fourth American woman to earn IFMGA certification, the highest professional qualification available to mountain guides.

Elizabeth Oakes Smart: IFMGA/UIAGM Mountain Leader

Liz Oakes Smart is an IFMGA/UIAGM-qualified mountain guide, ski mountaineer and climber. Her qualification allows her to guide worldwide. She has lived in Chamonix for several years, where she runs her own guiding company with her husband.

She has completed major ski mountaineering descents across Europe, North America and Asia. Highlights include the west face of the Eiger, the Couloir du Cosmiques and Glacier Rond in Chamonix, classic lines in La Grave, the Fuhrer Finger on Mount Rainier, and descents in Alaska’s Chugach Range. She has also skied from 7,200 metres on Shishapangma.

Alongside skiing, Liz is an accomplished rock climber. She has completed long free climbs in Yosemite National Park and Squamish, and climbed the Cathedral Traverse in the Tetons in a single day.

Experience the peaks for yourself

If the stories of these Lady Legends — past and present — have inspired you, our Resort Team can help you take the next step. We work with trusted local guide companies who can recommend routes that match your experience and goals.

If you’re new to the high mountains, a guided glacier hike offers a safe and exciting introduction to alpine terrain. More experienced climbers can explore more technical routes with expert guidance.

However you start, the mountains of Chamonix offer unforgettable experiences for every level.

Featured image of Henriette d’Angeville is © Guilhem Vellut, shared via Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic (CC BY 2.0).